SOLARIS first user meeting

About SOLARIS and the event

The SOLARIS synchrotron opened to users in Oct. 2018 and just had their first user meeting. It took place online from 9th to 11th of September 2020.

The EU and Poland granted 40 M€ to the Jagiellonian University to make SOLARIS, which is not much. But they managed to build a state-of-the-art machine anyway, in particular thanks to MaxIV in Lund (one of ExPaNDS partners), which openly shared the design they had just approved for the MaxIV 1.5 GeV storage ring.

They have 2 beamlines in operation, a Cryo-EM station and 7 beamlines in construction. The status of the machines is live on this website.

SOLARIS is part of LEAPS and of CERIC-ERIC with Elettra (another one of ExPaNDS partners), TU Graz and others from a total of 8 countries in central Europe (Czech Rep, Italy, Poland, Austria, …). CERIC-ERIC is one of PaNOSC’s partners. So all of us are tightly entangled.

It was an interesting user meeting, both in terms of content and of field experience for such online events. Here’s a selection of 4 talks, chosen because of the science (Cryo-EM and metallic hydrogen) or because of the speakers (XFEL and Elettra).

European XFEL, new X-ray source offering new research opportunities

Speaker: Thomas Tschentscher, scientific director or EU-XFEL

Some numbers on FELs and XFEL

FELs, with their ultrashort durations, from 1 to 200 fs, allow scientists to probe very fast movements and highly transient states. Their high intensities, from 0.1 to 1 mJ, are also sought-after. And finally there’s the transverse coherence, that electrons gain in the long tunnel (2 km for XFEL), which reaches less than 10 keV.

EuXFEL has 3 FELs and 6 instruments working in shifts - which is not so easy to orchestrate apparently. The electron energy ranges from 8.5 to 17.5 GeV.

Challenges

Challenges include of course high data rates but also high repetition rates of facility to improve data and possible data analysis services for users.

The biggest experiment so far produced a couple of PB in a week, when there is “only” ~75 PB of storage for now. The current goal is thus to reduce the datasets to only the high value data. Which is what Frank and Betty are developing for them, here in IT, using ML. They are very aware that PB can be neither transferred nor analysed easily so they’re not usable at such for many scientists.

XFEL and Poland

Poland is part of the XFEL where btw 7% of the scientists are Polish. There is a new ultra-speed link (100 Gbits/s) between XFEL and the NCBJ Swierk computing center (next to Warsaw). There are also foreseen collaborations for the Polish FEL construction (polfel), again with NCBJ.

Remote access to Research Infrastructure and Data

Speaker: Roberto Pugliese (PaNOSC, Elettra)

The future that is shaping up after COVID: scientists will have the choice to do remote or presence experiments.

Essential Remotisation project @ Elettra

Elettra has been working on remote data access and remote control of data acquisition computers with both remote desktops or cloud technologies. As a result:

- 60% of their 32 beamlines can do experiments remotely.

- Metadata is automatically captured for 32% of their instruments.

They also tried out new technology like telepresence robots which he admitted was just a fancy word for videoconferences with wheels. They are now studying voice user interfaces because talking is much more efficient than reading and writing on a web interface. A person can apparently say 20 000 words/day which is ~ half a book! He didn’t say if it was an Italian statistic because I’m not sure the average Hamburger is so verbose :grin:.

The feedback from Elettra’s beamline scientists on conducting remote experiments was:

- it is definitely more work for them,

- the relationship to the users can be difficult, the most difficult being the sample preparation,

- but that overall it works.

FAIR, ExPaNDS and PaNOSC

Roberto quickly presented what FAIR data was, how and why scientists should use PIDs, and the focus of ExPaNDS and PaNOSC in making datasets and analysis pipelines remotely available too.

Following a question, he said the typical 3 years duration of the embargo period on data comes originally from the duration of a typical PhD. But he reminded it could be changed by the principal investigator.

Cryo-EM and structural biology

Speaker: Sebastian Glatt, Max Planck research group in Krakow

Proteins having a ~10 nm diameter, they were traditionally studied with NMR spectroscopy or X-ray crystallography but now EM, that is electron microscopy, has revolutionised the field, in particular thanks to much better microscopes.

Single-particle EM means the sample contains very few proteins, with different orientations. In one ‘shot’, the electron beam take ‘pictures’ of those different angles simultaneously that you can then reconstruct into a 3D image of the protein.

Why cryogenic temperatures? Because otherwise the proteins are damaged very quickly by the radiation.

To be noted, the digital user office with a shared calendar system was very appreciated by the users and the IT team was warmly acknowledged.

Some numbers on the Cryo-EM unit at SOLARIS

- ~475 TB of data produced since Oct. 2019

- 1 dataset is 4-25 TB: they are trying to have a direct data transfer to the local computer center and ultimately to their national grid project ‘PL GRID NG’

- ~5000 L of liquid nitrogen used

- ~800 grids were frozen

- a 2Å-resolution was reached, which was awarded the best resolution in?

Being quite recent, they don’t have publications yet but very good datasets. In future prospects for SOLARIS, the new crystallography beamline will be complementary to the Cryo-EM unit.

Synchrotron infrared crystallography and imaging: opportunities and new challenges

Speaker: Paul Dumas, SOLEIL & CEA-DIF (former colleague of mine!)

IR vs other synchrotron light

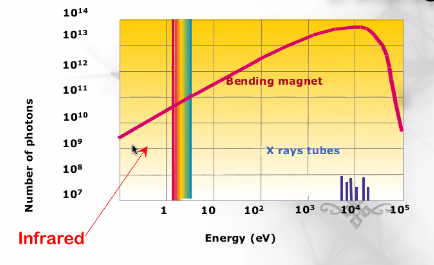

IR wavelenght’s domain is 1-500 µm. There is much less flux (= number of photons) in the IR region compared to X-rays and even compared to the radiation of a black body at 2000K.

But there are advantages to this low flux:

- We can study live cells and not destroy or even damange them. Incidentally, the main field of IR application is biology.

- IR can induce vibrational motions of molecules, which is very convenient to detect interactions.

- The resolution is very good: in the micron scale (~ half of the probing wavelenght).

And the low flux is compensated by a very good brightness (or brillance, which is the ‘focus’ or angle of the ray). The brightness of synchrotron IR is much higher than the black body’s at 2000K (2-3 times) so it is one of the main appealing features. Indeed, it allows for:

- a high signal to noise,

- a fast data acquisition,

- a resolution at the limit of diffraction.

Note from the talk by Nils Mårtensson on Max-IV and SOLARIS collaboration to add to this:

To have high brillance you need low electron beam emittance (< 10 nmrad for a 3rd generation synchrotron). To have a low emittance, the bending must be very gentle and you need to bend many times. That is why synchrotrons need a big circumference or if you can’t, there are tricks like dispersing in the straight sections. MaxIV was state-of-the-art with its multibend storage rings, which earned them a publication in Nature.

Paul’s idea for SOLARIS (he’s in the Scientific Advisory Committee) is to use X-ray and IR light simultaeously on a probe so shortcomings inherent to both domains can compensate each other.

Publication on metallic hydrogen from early 2020

Paul was one of the authors for this publication and he showed my former colleagues’ diamond andiv cells (DAC) which were used for it.

The pressure applied to the probe depends on the ratio between the diamond’s external and internal surfaces. So 100 bars on the external surface can induce up to 3 million bars on the inside surface. They managed to get above 2.5 Mbar without breaking the diamonds and detected solid hydrogen was formed.

To detect the state of the hydrogen, they observed the movement of electrons: they are free in metallic state, bound in molecular state. They only managed thanks to very bright IR light because with the pressure getting higher, the gap between bound electrons and free electrons becomes less and less visible.

Emerging techniques

Tomography is emerging in the field also. It takes a picture of a probe at each angle of detection that can later be reconstructed to a 3D image.

Final non-scientific consideration

Let’s finish on this note of Nils Mårtensson from Uppsala University saying:

What made Max-lab a success? The laboratory was small enough that the facility personnel and the users shared the same coffee room.